EFFICIENT IS THE NEW SEXY

A new lineup of energy-savers may not be the sexiest part of a new home, but reduced power drag has its seductions. The reason the most unglamorous features deserve the most attention is because savings from them helps afford trips, tuition, cars or even more house.

“I tell people if they’re going to spend money, spend money on insulation and conservation,” says east Orange County builder Robert Goderis. “The cost of energy is only going to get more expensive. These are the legacy costs you have to pay every month.”

As technology drives greater efficiencies, several new-home energy misers have become mainstream enough to affordably fit into both production and custom houses. In the guts of the home, what’s old isn’t new again — the old stuff is only becoming more obsolete by the day.

some highlights:

- • Hybrid water heaters increasingly compete with tankless ones as an efficient option.

- • Solar panels have gotten smaller, more powerful and less expensive.

- • A whole-home approach to conservation lets owners automate lighting and thermostats from the controls on a phone app. The words “I forgot to turn down the AC” should no longer be spoken in an era of programmable, WiFi-connected homes.

And while builders are quick to market themselves as energy-efficient, some features that once impressed buyers have become the norm.

Energy Star appliances, for instance, are more of a standard than a stand-out, says Hardwick General Contracting President Greg Hardwick, a board member of the Florida Green Building Coalition and past president of the Master Custom Builder Council.

LED lighting has become the expectation instead of the exception. Installed in homes, they can use at least 75 percent less energy and last 25 times longer than incandescent lighting, according to federal energy research.

Even the old standby — ceiling fans or pre-wiring for them — are still as integral as bedroom doors, but they now struggle to compete as an energy-saving feature. “I don’t think ceiling fans cool the room,” Hardwick says. “They just make your skin feel cooler.”

Other components of a sustainable new homes in Central Florida include:

a tankless job

Hybrid water heaters have a heat pump that “steals” heat from the room and returns cooler air, Hardwick says. When the demand for hot water is high, a hybrid water heater switches to standard electric heating.

The system is ideal for the garage and makes that space more comfortable, even while using minimal electricity. Units can be noisy, so they may not be ideal for interior spaces.

Tankless water heaters, Hardwick adds, have their place. But the return on investment varies and they tend to use more water — particularly with the promise of endless hot showers.

Here’s how they work: Turn on the hot-water tap and cold water travels through a pipe and into the “on-demand” water heater. A gas burner or an electric element heats it up and delivers a constant supply of heated water.

Gas-fired heaters can supply more water than electric ones.

The cold shower may come when the dishwasher, washing machine, sink or other showers demand hot water at the same time.

an app for that?

Earlier generations of programmable thermostats allowed owners to set one temperature for the daytime when fewer people were home, another for evening hours and yet another for overnight hours.

The idea was to stay comfortable while saving as much as 10 percent on bills by setting the temperature a recommended 7-10 degrees from the normal comfort zone for eight hours a day.

Now, a range of phone apps can program thermostats and zones within homes from anywhere. New technologies have put the controls at the fingertips of homeowners regardless of whether they’re at the beach or sitting on the back porch.

Forget to adjust temps while heading out of town? Just tap “vacation mode” on the phone app.

attic attention

Vasu Persaud, owner of Winter Garden-based EcoVision Homes, says it’s not expensive to simply install a higher grade of insulation into the walls and the attic, going with R-20 rated materials in the walls and R-40 for the roof.

“It’s a small improvement that lasts the lifetime of the home,” says Persaud. His company also layers the attic ductwork under insulation to better moderate temperatures for the air ducts, which remain accessible for repairs.

Homes also benefit from radiant barrier roof systems that help shield the attic, ducts and overall home from extreme temperatures. The barriers are made of a highly reflective material that reflects radiant heat rather than absorbing it.

They don’t, however, reduce heat flow in the way thermal insulation materials can, according to the federal energy department.

And spray-foam insulation has become more fine-tuned in sealing out heat — and cold — from the rest of the home. Builders also favor the foam for its effectiveness in reducing noise.

build that wall!

In East Orange County, Goderis is among builders who fortify exterior concrete-block walls with foam to better withstand Florida temperatures. The technique has been around for years — but the materials have become more effective.

“We do core foam in the block walls. It’s really permeable and goes in the consistency of thick soap bubbles,” says Goderis, whose workers drill every 8 inches into the blocks to pump in the material. Doing so more than doubles the R-rating of typical concrete walls, he added.

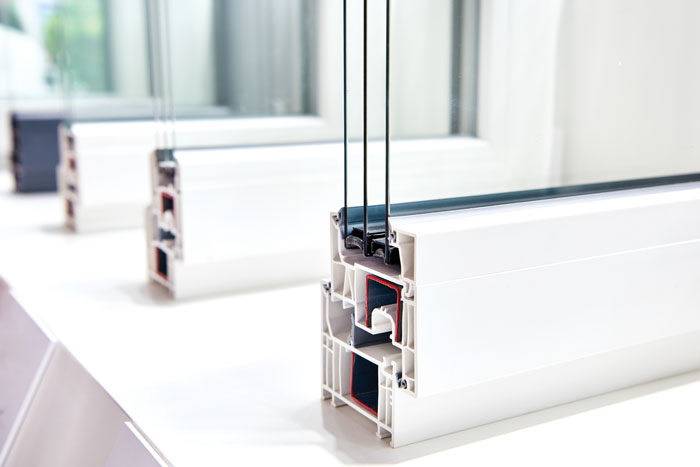

double-pane delight

Passive solar is a home orientation that brings in sun from the southern skies during the winter while minimizing the summer sun’s impact with overhangs and window placement.

But in Central Florida during the last decade, the choice of homesites has dwindled — and homesites that are available are generally smaller — so buyers don’t usually get much flexibility in placing the home for the optimal solar exposure.

With those limitations, window materials and styles have become increasingly important. Buyers should now expect double-pane windows covered with low-emission film to reduce the magnifier effect of windows from years ago.

“I don’t think you can even meet (building) code with single pane windows anymore,” says Hardwick.

HERE COMES THE SUN

Many Central Floridians have had the knock on the door (or the unwelcome cellphone call): “I’d like to talk to you about solar.”

Solar technologies have evolved quickly, with a growing number of suppliers getting into the business of topping roofs with photovoltaic panels in order to harness power and reduce utility bills.

Hardwick says he saves about $300 monthly on his own home and expects a full return on his $30,000 solar investment within 10 years of installation.

“My take on solar is that it’s more about designing a system for your home and maximizing the power it can produce,” he says. “It depends on weather and trees.”

Solar panels now come with more watts per module and tax credits are available, although they may have softened in recent years, he adds.

Options, costs and incentives vary widely, and experts advise homebuyers to study their roof warranties and the return on investment before proceeding with what can be a major commitment. Buyers and owners can also weigh lease options as well.

Orlando-based Brite Homes builds with hybrid water heaters, foam-filled concrete block, LED lighting and other conservation features. After installing solar in homes underway in Palm Bay and Palm Coast, the company opted to make the feature standard, says Christopher Sterns, the firm’s team lead success manager.

Sterns says his own utility bill had been $300 to $400 when he lived in a 3,000-square-foot Windermere home that was decades old. He now lives in Brite Homes’ North Port community near Sarasota and pays about $58 monthly to keep his 1,800-square-foot home comfortable.

Like many owners who have invested in power-saving devices, Sterns notes that part of his bill covers a surge protector, and it may also run “high” with his three freezers in his garage.

And then there’s the constant temperature setting in his house — a comfortable 73 degrees.

WHAT DOES GREEN BUILDING CERTIFICATION REALLY MEAN? LET’S FIND OUT.

Like labels on a shirt or a purse, an increasing number of homes now carry a certain “green” brand. Homebuyers see many such seals of approval, ranging from the pinnacle LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification stamped on this year’s New American Home in Winter Park to production builders with their own seals of environmental approval.

“All the certifiers are good in some ways,” says longtime Orlando custom builder Greg Hardwick, president of Hardwick General Contractors, who recently won a top-level green award from the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). “It’s like a Coke and Pepsi thing.”

Ratings generally measure air leakage, appliance efficiency, insulation and lighting – all features that can shave a home’s monthly utility costs. The popularity of green certifications has spread throughout Central Florida’s homebuilding industry.

Some examples:

David Weekley Homes works with TopBuild Home Services on its Environments for Living Program, which touches on everything from efficiency to air quality to paint durability. KB Home and Meritage Homes use Energy Star certification. Maronda Homes has its own brand called Bee Smart.

“I think they all have their place, depending on what’s the best fit,” says C.J. Davila, executive director of the Florida Green Building Coalition (FGBC). While LEED certification can be pricey, it’s better suited for large, commercial structures or for production builders who want to standardize their construction across the country, Davila adds.

FGBC is a Florida-based nonprofit organization whose mission is to create a statewide green building program with environmental and economic benefits. It has an online database of Florida green projects, products and professionals, and holds an annual conference, GreenTrends.

Using Florida stakeholders and member committees, it has created the Florida Green Home Standard, a designation for new and existing homes. Projects are scored on stewardship activities in eight categories, with minimum scores in each category.

Categories include energy performance, water conservation, site conditions, healthy interior materials and disaster mitigation (the ability to withstand a natural disaster or a termite invasion). A score of 150 or more is needed for certification.

Davila advises homebuyers to research any certification programs that fall under the umbrella of services provided by the homebuilder: “It’s like a car company coming in and telling you, ‘This is the best car you can ever buy’.”

Most ratings rely on independent tests that seal up a home and blast air inside to determine how much leaks out. Most also rate homes with a HERS (Home Energy Rating System). And the day may come when the score is considered for home appraisals.

Hardwick, a director for FGBC, says the council’s certification is more applicable to the state’s specific climate, while the US Green Building Council’s LEED certification is better known for its detail and prestige.

The costs of getting a home certified can range from about $100 for the FGBC certification to thousands for the LEED certification.

Central Floridians can see what the top industry rating looks like on Morse Boulevard in Winter Park. A chic three-story home — which started life as adjacent townhomes — was built by Phil Kean Design Group for NAHB’s New American Home. With a rooftop that looks like a solar farm, the showcase of design and efficiency won the highest LEED certification.

It’s also possible to get the features required for LEED certification without as much of the cost. Vasu Persaud, who owns EcoVision Homes LLC, says homeowners can get the elements of a top-certified home without the builder having to pay for certification — a cost that is likely passed along.

Buyers need to talk to builders about features like solar, insulation, appliances and the home’s ability to retain thermal qualities, he says, adding that “you can build a LEED-level house and not be LEED certified.”

Adds Persaud: “Certifications are mostly moving the conversation forward collectively.”