FOR FORMER JAGS, JACKSONVILLE REMAINS HOME, SWEET HOME

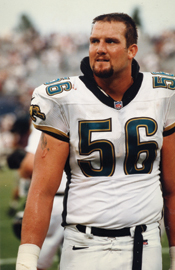

Jeff Lageman never imagined this. Not when he was growing up in Sterling, Virginia, and certainly not while he was playing for the New York Jets in the early 1990s.

Jeff Lageman never imagined this. Not when he was growing up in Sterling, Virginia, and certainly not while he was playing for the New York Jets in the early 1990s.

Back then, playing professional football in Northeast Florida wasn’t a possibility. And as for making his home in Jacksonville, Florida...

Well, even when Lageman became one of the first high-profile free agents for the expansion Jacksonville Jaguars in the spring of 1995, long-term residency in Northeast Florida wasn’t on his mind.

But that changed, and it changed pretty fast.

“In those early years with the Jaguars, we got accepted into the community real quick,” Lageman, now an analyst for Jaguars Radio, says. “We just loved it. There was an amazing feeling in this town in 1995 and 1996 being a Jaguar. That was special.”

Lageman is far from alone. The success the Jaguars had early in their history — four playoff appearances and two AFC Championship Games — may seem far away, but the feeling Jaguars players have for Jacksonville has remained to a remarkable degree.

The team has been in Jacksonville 18 years, and during that time, players have become part of not just the franchise, but the community. The roster includes Lageman, former All-Pro left tackle Tony Boselli, three-time Pro Bowl quarterback Mark Brunell, former All-Pro left tackle Tony Boselli, three-time Pro Bowl quarterback Mark Brunell and hard-hitting safety Donovin Darius.

There’s also kicker Mike Hollis, punter Bryan Barker, defensive tackle Don Davey, center Dave Widell, defensive end Eric Curry, tight end Damon Jones, defensive end Paul Frase, linebacker Lonnie Marts, running back James Stewart, center Greg Huntington and tackle Todd Fordham.

All played for the Jaguars, and most could live anywhere they choose. Some left briefly for other teams, and even other careers, but now — whether they live in Jacksonville Beach, Ponte Vedra, Queen’s Harbor, Jacksonville Golf and Country Club or Marsh Landing — all call Jacksonville home.

“Jacksonville, if you just visit it, you miss the greatness of the city,” says Boselli, who lives in Ponte Vedra with his wife, Angie, and their five children. “But if you stay for any extended period, you realize there aren’t many places this well-rounded as far as the climate, the outdoor activities and the location.”

Boselli also likes the people and the city’s family ambience. “There are so many great things that make it a great place to live,” he adds. “Once you get here, it’s like, ‘Why would I ever leave?”

Some have stayed for business opportunities. Some have stayed for golf. Many of the members of the 1995-1999 teams, the most successful era in franchise history, are still beloved.

Lageman is one of those players. But long before the town embraced him, he embraced the town — once he got to know it.

Through that first off-season, then-Head Coach Tom Coughlin worked the players pretty much constantly, he recalls, so there was little time to become familiar with the community.

The following offseason, however, there was more time. Lageman, an avid outdoorsman who has hosted an outdoors radio show since the mid-1990s, quickly liked what he discovered.

He fell in love with not only Florida’s fishing — “off the charts here,” he calls it — but with the proximity of hunting opportunities in Alabama, South Carolina and South Georgia.

“This is Southern hospitality down here,” Lageman says. “There are some great people in New York, don’t get me wrong. But the Southern feel of this town, that’s what I grew up with.”

Boselli’s Jacksonville story is different, but with a similar ending. The first draft choice in franchise history, he and Angie moved immediately to Jacksonville during his rookie season in 1995.

For nearly seven years, Boselli was pretty much the face of the franchise. But when the team let him go to Houston in the 2002 expansion draft, Boselli — disappointed about being released — sold his house in Jacksonville.

He, Angie and their children lived in Houston for a short time. Then, following his retirement in 2003 because of shoulder problems, they moved Nashville, Tenn.

“We loved Houston — it was a great place to live,” Boselli says. “We loved Nashville. There were some great people. But after about three years away from Jacksonville, we were here and staying with some friends. We were walking on the beach. I said to Angie, ‘What do you think about moving back?’ We looked at each other and realized, ‘This is the only place that felt like home.’ ”

Three weeks later, they were back in Northeast Florida.

Boselli, who grew up in Boulder Colo., now considers Jacksonville to be his hometown. The first player inducted into the team’s Pride of the Jaguars, he now works for Westwood Radio and runs the Boselli Foundation, which now operates two local Youth Life Learning Centers.

Darius, a first-round pick in the 1998 NFL Draft, played seven seasons for the Jaguars. Like Boselli, he runs a foundation in Jacksonville — the Donovin Daris Foundation, which works with youth in character development, education and athletics.

Also like Boselli, Darius comes from a place that seems to have little in common with his adopted hometown. He grew up in Camden, N.J., and played at Syracuse University. Although he had an uncle living in Jacksonville when he arrived as a rookie, he had few ties to the community.

But after he and his family moved to Jacksonville, they remained. “It’s a good church community, and I just felt like there was a tremendous opportunity,” he says. “Sometimes, guys stay because they want something different. There’s a natural feel to Jacksonville. You get a chance to experience the beaches, and all of the nature.”

Darius also loves the city’s Southern hospitality. “You have a chance here to make an impact,” he says. “You’re part of a community. People here are willing to open up their arms to you, and that’s why a lot of people stay.”

Will people be surprised to hear that? Those who know little of Jacksonville, perhaps. But the things ex-Jaguars players say are the same things other residents say — Jacksonville is a special place, one often misrepresented by people who don’t know better.

Lageman smiles at this, because long ago — long before he arrived in Jacksonville — he was one of those people. As a kid, he hated the idea of Florida. He visited relatives in Southwest Florida each summer, and his opinion was that the state was too sandy and certainly too darned hot.

Now? Well, now Lageman and many of his former teammates feel differently about a city with which they were once unfamiliar and even a little apprehensive.

“My roots are here,” Lageman says. “I bought a house in 1995. I’m still in that house today and I plan on being in that house for a very long time. I never felt that way in New York, not for a minute.”

IMPACT GOES FAR BEYOND THE STADIUM

IMPACT GOES FAR BEYOND THE STADIUM

Shad Khan’s vision is nothing if not forward-thinking. So, when Khan purchased the Jacksonville Jaguars in January 2012 and set about refining the team’s overall mission statement, it wasn’t surprising the statement had a mix of old and new.

Since their 1995 inception, the Jaguars have been one of the NFL’s most charitable franchises, giving generously to groups supporting local youth. While Khan wanted that to continue, he wanted something more — for the Jaguars to be not only charitable to the community, but a critical player in its overall future.

“Besides helping the young, he (Khan) wants to be a partner with the community,” Peter Racine, president of the Jaguars’ Foundation, the team’s charitable arm since 1995, says. “The way Shad looks at it, he has a window of 15 or 20 years. He wants to look back and say, ‘How did I help the city of Jacksonville to be better?’ ”

How do you quantify the NFL’s value to a community? How does the NFL improve a city?

Many ways. There’s community pride, something people from all neighborhoods can share, but there’s tangible stuff, too. Beyond the estimated $130- to $200 million economic impact annually, there are the millions the Jaguars have donated to low-income children in nearly two decades, and the hundreds of annual community appearances by Jaguars players, who are directly touching lives.

Among the local programs to which the Jaguars have contributed in the nearly two decades since the team’s 1993 founding:

More than $16 million in grants have been awarded to programs serving low-income children. Those programs encompass child-abuse prevention and after-school activities as well as Boys and Girls Clubs and Big Brothers Big Sisters of Northeast Florida. “We’re a major funder in the community,” Racine says. “There are small programs that our $20,000 grant is a significant part of their budget. It’s a leg up in the nonprofit community — a substantial leg up.”

About 1,000 reduced-price tickets per season have been provided to the Greater Jacksonville area USO as part of the team’s Honoring Our Troops program. In addition, 100 or more seats every game are made available to families with mothers or fathers deployed in military service or just having returned.

Approximately 5,000 children a year “earn” a ticket to a Jaguars game through the team’s Honor Roll program, a value of $430,000 if the tickets were sold. Students earn the seats through community service projects and through a pledge not to use drugs, tobacco and alcohol.

Eight community, Police Athletic League and Pop Warner football fields have been built or renovated through NFL Field Grants and LISC — Local Initiative Support Corporation — grants at a value of more than $760,000.

A $3 million NFL “Youth Education Town” was built for the Super Bowl in 2004, funded from $1 million from the NFL and $2 million from the Jaguars.

More than $900,000 in combined grants — $200,000 from the NFL and $700,000 from the Jaguars — in after-school fitness and nutrition grants were awarded to middle schools around Jacksonville.

In addition, the team recently” “adopted” Andrew Jackson High School, an inner city school that was the lowest-performing in the state. Since the adoption, staff, players and coaches have visited the school, establishing a Jaguars “reading den” with a continued to commitment to rebuilding pride and helping the school perform at a high level.

“Any other football team could do it, but not every other football team is doing it,” Racine says.

Since Khan’s arrival, the team has also turned its focus toward civic improvements. This season the team contributed $74,000 through LISC, which is being used for community revitalization on the Eastside and the Northside. Next year, LISC will receive $100,000.

The Jaguars are also participating in the Jacksonville Community Council’s “Jax 2025” project, a community-wide initiative focused on envisioning what the city will become over the next decade.

“The Jaguars want to be part of the downtown development,” Racine says. “They want to be part if the revitalization of low-income neighborhoods in this area. He (Khan) wants Jacksonville to be on the international map, and he wants it to be a better city.”

Kahn believes the success of the city and the success of the Jaguars are all tied in together, adds Racine. “We want to be a part of improving the whole quality of our city,” he notes. “As the Jaguars improve, our city improves.”

As the team and community improves, fans in Jacksonville also may notice one more aspect of the Jaguars’ community outreach. Considering the importance of the military to Northeast Florida, it’s not surprising that the team is stepping up its support of the armed forces.

The NFL recently has increased its commitment leaguewide in this area, but under Khan, the Jaguars are doing even more. One of Kahn’s first major moves as owner was to enter a partnership with the city to provide a grant of $1 million a year to help veterans returning to to the region transition to civilian life.

“It’s really about growing with the community,” Racine says. “We want to win, of course, but the team is bigger than just the wins and losses on the field. That’s something people don’t get sometimes, and people don’t have to get it, but it’s true.”